As soon as we entered the grounds of Uxmal, we stopped. This first sight of the Pyramid of the Magician was so much more. . .well, magical than anything we had seen so far. In fact, the best term to capture my response might be rapt—especially apt since we visited the site on the day of the predicted Rapture.

Pirámide del Enano (Pyramid of the Dwarf, also called Pyramid of the Magician)

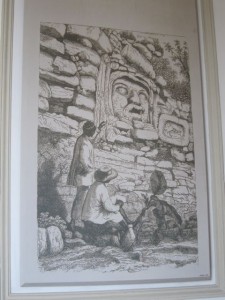

As we’ve found so often, Stephens anticipated our reaction. He describes his first experience of Uxmal this way:

We took another road, and, emerging suddenly from the woods, to my astonishment came at once upon a large open field strewed with mounds of ruins, and vast buildings on terraces, and pyramidal structures, grand and in good preservation, richly ornamented, without a bush to obstruct the view, and in picturesque effect almost equal to the ruins of Thebes. . . .The place of which I am now speaking was beyond all doubt once a large, populous, and highly civilized city. Who built it, why is was located away from water or any of those natural advantages which have determined the sites of cities whose histories are known, what led to its abandonment and destruction, no man can tell. (John Lloyd Stephens, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas & Yucatán, 1843)

Stephens captures the elements that still shape response to this site: difficulty of access, making the encounter with fabulous ruins even more impressive; intimacy, helping modern visitors to picture the ways the Maya might have lived there; architectural vocabulary, rendering the site more accessible to those familiar with classical motifs; and of course the essential romance and mystery that have been projected onto the Maya for two hundred years. (Towards the end of our trip, Heath helpfully told me that my preference for Uxmal was entirely predictable: the site’s size and relative remoteness from the contemporary tourist trail, combined with the relative simplicity of its Puuc-style architecture, make it a prime introduction to romancing the Maya.)

We’d driven down from Mérida early in the morning, having already learned that the only way to beat both the heat and the crowds was to arrive the minute the sites opened (usually at 8 a.m.). We arrived in good time; still, Uxmal was initially less appealing than Chichen Itza—which we first glimpsed through the lovely colonial archways of our hotel, and which we entered by wandering up a pathway lined with ancient Piich (elephant ear), mango and acacia trees.

By contrast, Uxmal appeared, from the outside, much more controlled and regulated. To enter, we had to pass through a concrete patio to buy tickets and be tempted by a range of tourist shops.

Uxmal entrance

Once we entered the site itself, though, our experience of it was transformed. Although Uxmal has been extensively restored so that tourists can imagine how it (might have) originally looked (see Jo’s post “Who Built Uxmal” for more on this), ironically it seemed less institutionalized than Chichen Itza: the crowds, ropes, and signs that controlled our experience there were far less intrusive here.

To some extent, this is simply an issue of access: Uxmal, a six hour drive from the “Maya Riviera,” is somewhat off the tourist trail. During our visit, we saw so few people that we came to know them a bit (there was the German couple in matching turquoise shirts, for example, or the Mexican woman whose t-shirt proclaimed “I only date nerds,” while the guy at her side reinforced this sentiment by constantly lecturing her on what she was seeing). The lack of crowds meant that this site seemed more peaceful and personal than others we visited. (But why do tourists revel in the experience of spaces free from other tourists? Interestingly, not all of us were bothered by the crowds at other sites; Matt noted that he could “filter them out,” while I found this difficult.)

Fern at Uxmal

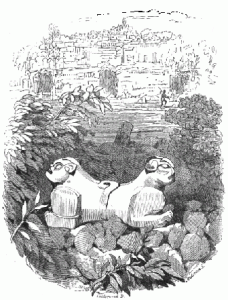

In addition to providing a less regimented experience of its space, Uxmal is smaller than Chichen Itza and so feels more intimate. Although our first sight of the ruins was spectacular—immediately on entering the gates, you’re faced with the impressively sized Pyramid of the Magician—most of the site is organized into quadrangles. So after moving past the pyramid, we entered an open plaza facing the building dubbed, by the Spaniards, Casa de las Monjas or Nunnery because of its many small rooms or cells. Many of Uxmal’s structures are long and low, with clean–almost classical–lines. Wandering through the open space, entering the small, cool rooms with their neat piles of as yet unreconstructed stone blocks, I disturbed only a few iguanas.

Uxmal iguana

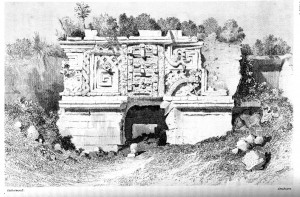

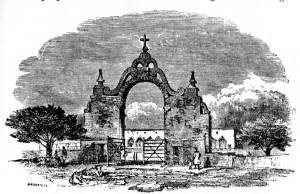

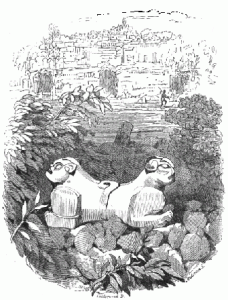

Later, climbing the gran pirámide, we gained an amazing view of the entire site, including a ceremonial archway that seemed to lead to a sacbe, one of the raised roads built by the Maya to connect their cities. The site’s clear, simple organization highlighted the ways that Uxmal, built in Puuc style of the Late Classic period (roughly 600-900 AD), is less ornate than Chichen Itza; its details reinforced this impression, since in place of stylized skulls and heart-devouring jaguars, Uxmal’s buildings feature geometric motifs like the latticework or mat design associated with power, as well as beautifully detailed (and notably peaceful) depictions of animals like the twin cats in front of the Palace of the Governor–

Catherwood, Double Headed Lynx

–or the small round turtles marching round the façade of the House of the Turtles:

House of the Turtles, Uxmal

House of the Turtles, Uxmal (detail)

Stephens shares some of the stories behind the buildings, too, and for those who read his or other versions, the tales help to connect visitors to the site. The Pyramid of the Dwarf was, so the Mayan legend tells us, built by a dwarf who, with the help of his mother the bruja or witch, challenged the ruler of Uxmal and won—it’s a kind of David and Goliath tale of a dwarf boy and a woman combining their wit and skill to defeat a powerful king. Then there’s the myth to explain the House of the Turtles: supposedly, the Maya regarded turtles as similar to humans in that they suffered during months of drought and therefore prayed to the same god humans did, the rain god Chaac, who covers the buildings of Uxmal (and no wonder, since there are no cenotes or other reliable sources of water at the site).

In his essay “Putting the World in Order: John Lloyd Stephen’s Narration of America,” my colleague Miguel Cabañas explains Stephens’ goal in “discovering” these lost (from an outsider’s perspective) ruins:

Both elegiac and commercial forms of exploitation join the peripheries to the mainstream as American cultural artifacts. The simultaneous fetishization and commodification of indigenous cultures reveal a dual motive in Stephens’s travel narratives: the narratives mix mythmaking and pragmatism in a contradictory quest that asserted the project of modernization by re-appropriating the value of premodern societies. (12)

Miguel makes me wonder: what quest are we on today, as we follow in the footsteps of these Anglo-American explorers? As we tour these archeological sites, aren’t we participating in the same fetishization and commodification of indigenous cultures that Stephens carried out in 1843 (see Matt’s “Who Owns the Maya” posts)?