Why travel in the footsteps of Stephens and Catherwood or anyone else, for that matter? I think footsteps add historical depth to a journey. They help us think about the space between the past and the present.

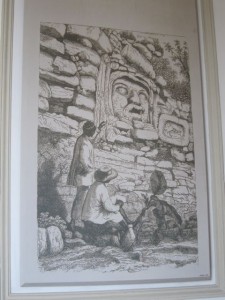

Others have felt the same way. When we entered the late nineteenth century neo-classical/French baroque Museo Regional de Yucatán, we were greeted by large reproductions of Catherwood’s engravings. (Indeed, we have found reproductions of the engravings throughout the Yucatán — on restaurant menus, the walls of our hotel rooms, signs at archaeological sites, magnets in gift shops and more). Everywhere the reproductions take on a different meaning. In the museum, they remind me of Stephens and Catherwoods’ plans to display the Maya material that they collected in the United States. Catherwood’s images in the museum resonate with the history of the collection, display, and looting of ancient remains from the Yucatán.

Stephens wrote often about his work collecting Maya objects. Preparing, storing, packing and shipping pieces of the monuments, he said, was the most arduous task of his journey. His treasures were destined first for Catherwood’s Panorama on Broadway in New York (a display for tourists that included a ten thousand square foot mural of Jerusalem and another of Thebes! Catherwood, it seems, earned part of his income from this attraction and another one similar to it in London). After the exhibition of the objects in New York, Stephens planned to ship them to the National Museum in Washington D.C.

In one passage Stephens recounted how he packed off a rare sculpted beam from Uxmal to the U.S.:

…I had determined not to let the precious beam escape me. It was ten feet long, one foot nine inches broad, and ten inches thick, of Sapote wood, enormously heavy and unwieldly. To keep the sculptured side from being chafed and broken, I had it covered with costal or hemp bagging, and stuffed with dry grass to the thickness of six inches. It left Uxmal on the shoulders of ten Indians, after many vicissitudes reached this city uninjured and was deposited in Mr. Catherwood’s Panorama.

(Stephens, Incidents of Travel in the Yucatán, Volume One, page 103.)

Unfortunately, a fire destroyed Catherwood’s Panorama before Stephens could transfer his Maya treasures to the National Museum. Stephens laments:

…on the burning of that building…this part of Uxmal was consumed, and with it other beams afterward discovered, much more curious and interesting; as also the whole collection of vases, figures, idols, and other relics gathered upon this journey…if I were to go over the whole ground again, I could not find others equal to them. I had the melancholy satisfaction of seeing their ashes exactly as the fire had left them. We seemed doomed to be in the midst of ruins; but in all our explorations there was none so touching as this.

(Stephens, Incidents of Travel in the Yucatán, Volume One, page 103.)

Stephens and Catherwood were the first in a long line of foreign collectors of Maya antiquities. Many remains from Chichen Itza, for instance, are displayed today in Harvard’s Peabody Museum. Edward Herbert Thompson, an American who was inspired by Stephens’ books, purchased Chichen Itza in 1904 and subsequently shipped many of his finds to Cambridge.

Unlike the Peabody, the Museo Regional de Yucatán is small. It opened in 1959 and has seven elegant galleries on the first floor that display a modest collection of Maya material. Here, I found much that helped fill out the picture of the daily life of the ancient inhabitants of this region: spindle whorls, wooden planting sticks hardened by fire, images of Maya women grinding corn, cocoa beans, red shells and green stone beads used for money, and human bones.

But the museum itself also resonates with more recent history. Its architecture is colonial; its size speaks eloquently about the movement of Maya artifacts to museums in the United States, Europe, and Mexico City; and its organization attests to the role of archaeology in the creation of knowledge about the Maya past.